Intellectual History of the Law School

Copyright © 1993, Law and Economics Center

Introduction

Modern American legal education is usually said to have begun with the advent of Christopher Columbus Langdell as Dean of the Harvard University Law School in 1870. His innovations there were to determine the course of formal training for lawyers in the United States from then until now. Indeed in the fundamental approach to curriculum, style and organization, American Law Schools still heavily reflect much of what happened at Harvard over 120 years ago.

Central to the Langdellian revolution was the view that American law schools should primarily and predominantly be concerned with training practicing lawyers. Langdell’s idea was that this could best be accomplished by giving students a “scientific” view of the body of law, and this view in turn led to the development of “casebooks” and the “case method” of teaching, since cases, mainly the opinions of appellate courts in Anglo-American jurisdictions, embodied the law. By appropriate organization and analysis of this material, it was possible, according to Langdell, to learn the “science of law.” This was, of course, spurious science, but the pedagogical powers of the “case system” proved so attractive that it persisted long after anyone still claimed that it had any scientific validity. Indeed it remains the dominant, though no longer the exclusive, mode of instruction at every law school in America to this day. For 120 years, the intellectual style and, some might add, even the distinctive combative personality of American lawyers, has been largely determined by this particular pattern of legal education.

But in spite of the enormous success this approach has had, as measured by its adoption and its viability, today we know that there were a number of things wrong with the approach and the education style it engendered. By the 1920’s a group of legal scholars who came to be known as the American Legal Realists raised increasing objection to both the theory and the practice engendered by Langdellian jurisprudence. Much of this concern had to do with the behavior of judges, the mystique of the common law, and the idea that case law would always evolve into appropriate rules for resolving the disputes clients brought to lawyers. Thus a fundamental premise of Langdellian jurisprudence came to be doubted.

Manifestly, this new skepticism began to affect education and pedagogy. And as Legal Realism came by World War II to be the dominant view of American law professors, it was clear that much of the older approach would have to be reevaluated and reformed. Certain things became very clear, such as the lack of realism in a pure casebook approach to a subject in law school. The advent of the large-scale use of administrative law by government at all levels, the increasing suspicion of the total detachment of judges, the explosion of both federal and state legislative approaches to social problems, and the realization that lawyers needed some knowledge that went beyond a simple ability to find and parse cases all conspired to force a reevaluation of the sacred cows of legal education.

This new realism, as it came to be called, also had certain traces of academic self-interest in it. Law professors of the old school could hardly lay claim to being either scientific or especially scholarly in their pursuits. After all, most of their published writing (jurisprudence and legal history were the principal exceptions) was exactly the same sort of analysis that practicing lawyers did, the main difference being that the professor got to choose his or her own topic. Occasionally a particularly brilliant insight or new form of analysis would be reflected in a law review article, but without the same fanfare that could also happen in a brief or an opinion. The Legal Realists scored heavily by inferentially accusing American law professors of being intellectually unsuited for academic life.

By the late 1940’s most professors in the more influential law schools claimed to be Legal Realists. But there was a peculiar irony to this claim. Try as they might, most law professors could do little more than bemoan the intellectual bankruptcy of American legal scholarship. They tried many approaches to make law more intellectual and more in tune with current academic fields. Most of this had some small measure of success, and vestiges of it remain even today. For instance, a number of Legal Realists thought that Freudian psychoanalytic theory would illuminate law in a massive way. But today that work continues almost exclusively in the field of criminal law, and even there it has had to reflect modem post-Freudian skepticism.

Law and sociology had a longer and more successful run, and the Law and Society movement is a dominant force in the scholarly work of many law professors today. It does, however, have some of the same shortcomings of sociology generally, that is, it is a tool for organizing and describing complex social data; nor does it contain a distinctive technique for analyzing causal relationships. There are no analytical models in sociology, and, therefore, its utility as a tool of law analysis is severely limited. What was wanted was an approach to law that would allow scholars to predict the effects of specified changes in the law and to compare alternative approaches in terms of some specified social goal.

It is for the last reason especially that certain newer approaches to legal issues have proved attractive. For instance, dissatisfaction with traditional norms of property and private contracting have largely furnished the impetus for Critical Legal Studies. A recognition of the utter historical disregard for the interests of women in Anglo-American law has led to a rich new feminist jurisprudence, and similar contributions are being made in the area of racial minorities and the law. Yet goal-centered as these new schools of jurisprudence may be, none has significantly responded to the Legal Realists’ quest for a rigorous scientific (and non-political) apparatus, even one susceptible to empirical verifications, in the manner of the natural sciences.

One approach to law analysis has offered such a powerful tool, and that is the approach generally known as Law and Economics. Not only has an economics approach to law offered legal scholars intellectual and academic credibility, it has also enormously influenced the substance of many areas of law. Unlike the other “law and’s,” Law and Economics has the potential to be scientific and empirical in its pronouncements and non-political in its judgments. As anything else in the scholarly ferment, it can, of course, be abused, but the tools are so powerful and have proved so useful both in scholarship and in practice, that it is hard to imagine law ever again being free of the influence of the techniques and findings of objective economic analysis. This influence has become so pervasive, and its role in modern legal education (particularly at George Mason) so dominant that it is important to this story to understand generally how this development occurred.

The Origins of Modern Law and Economics

Law and Economics seems such an obvious derivative of Legal Realism that its origins would seem to be intimately connected to the ascendance of Legal Realism in American law schools. But nothing could be further from the actual story of the beginnings of Law and Economics. Indeed none of the important lights of the Legal Realist movement, such as Karl Llewellyn, had much knowledge of or interest in economics. Sociology, psychology, and anthropology were the social sciences of choice for this group. Some of the most important of these scholars were actually hostile to the early development of Law and Economics, though it is possible that this had more to do with ideology than with scholarly criticism.

The reason that Legal Realism is so important to the development of Law and Economics is that it had already greased the path for such developments and made the entry into mainstream legal education of new disciplines a far, far easier matter than would otherwise have been the case. So while none of the well-known Legal Realists predicted in any sense that economics would prove to be the most powerful of the intellectual allies of law, the idea of merging law and social science was already accepted by the most influential academics in law.

The faculty of the University of Chicago Law School was no exception to this generally prevailing view. Seminars in anthropology and psychoanalytic theory were very much in vogue. But a peculiar set of circumstances, in many ways purely accidental, caused that school to be the founding site for Law and Economics. In 1947 a brilliant economist named Aaron Director left wartime service with the government in Washington and sought an academic position. His reputation as an incredibly brilliant theorist was well known at Chicago, and his friends there made a concerted effort to have him hired by the economics department. There was one big problem, however: he did not have a Ph.D. degree and that seemed to be an absolute requirement for a position in Chicago’s economics department.

As it happened, a rather well-known economist, Henry Simon, had been a member of the Law School faculty (and apart from this fact had little else to do with the development of Law and Economics) and had recently died. Director’s friends were able to have him appointed to the position created by Simon’s death, since the idea of an economist on the law faculty had by then been almost taken for granted at Chicago.

Prior to Simon and Director, one other economist, Walton Hamilton at the Yale Law School, had been a member of a law faculty, but apart from precedent value, he had little to do with the development of Law and Economics. John R. Commons, an economist at the University of Wisconsin, also wrote widely about the economics of law but always in the so-called “institutionalist” tradition, which for a variety of reasons not germane to this story, never blossomed into anything like a jurisprudential movement or even, in its original form, a viable school of economics. All of the significant action in the early development of Law and Economics centered around Aaron Director at Chicago.

The principal field of law that had a direct overlap with a field of economics was antitrust law. That was, at the time, perhaps the only and certainly the major law explicitly stated in terms of an economic test (“monopoly” or “attempt to monopolize”). It is not surprising then that Director gravitated first to that field, and that, since his office was in the library stacks, he did this by beginning to read antitrust opinions. He noticed that over and over again the judges’ use of economics was faulty at best and that rigorous economic analysis of the facts stated in these opinions would often lead to a different conclusion than the court had reached.

As Director studied more and more cases, he also found himself developing new analytic techniques relevant to the antitrust field. His analysis was so powerful and so unusual that it began to be discussed seriously by most of the faculty at Chicago. Professor Edward H. Levi invited Director to team teach the antitrust course with him, but many other members of the faculty at the time were even more influenced by the new form of analysis Director suggested for dealing with case material. Thus economics began heavily to influence such courses as corporation law, bankruptcy, securities regulation, labor law, income tax and torts. [1]

After 1952, perhaps because of the influence of Karl Llewellyn, who was hostile to the economic approach at Chicago, or perhaps because the faculty believed that economics had become too intellectually dominant, the school began to pull back from an exclusive interdisciplinary interest in economics. Nonetheless, for the next fifteen or so years, what we now call Law and Economics was almost exclusively associated with the University of Chicago Law School.

Director’s work was also part of a general resurgence of interest in microeconomics (the study of private individual and firm responses in market settings) at the University of Chicago, and it came to be referred to, often derisively, as the “Chicago School of Economics.” That response was and is typical of the response to any paradigmatic change in a scholarly field, since new ideas are often threatening to established scholars or those with intellectual capital they wish to protect. Today, as this form of economic theory has established itself as central to the entire discipline, the term “Chicago Economics” is rarely if ever heard among knowledgeable economists or Law and Economics scholars. (This is not meant to imply that there are not still serious differences among Law and Economics scholars on substantive points, only that there is no longer a general belief that one type of analysis is biased or ideological or inappropriate.)

Until the late sixties and early seventies, the University of Chicago Law School was about the only place where serious scholarship in what is now called Law and Economics was going on. There were a few Chicago graduates, like myself, who wrote regularly in the Law and Economics idiom and who taught at other schools, and by then several law schools, most notably Yale, had imported economists to teach both basic economics and antitrust law. Also Yale had hired the first law professor with both a J.D. and a Ph.D. in economics, Guido Calabresi, now its Dean and one of the most important figures in the development of Law and Economics.

Four Major Events in the Development of Law and Economics

Four events, all occurring near the same time, largely explain the almost explosive growth of Law and Economics at about this time, though one is hard pressed to find anything more than coincidence in their timing. The first of these was the revival of the Journal of Law and Economics at the University of Chicago under the editorship of Professor Ronald Coase after the journal, under Director’s editorship, had failed to appear for several years. Coase had been hired as Aaron Director’s replacement on the latter’s retirement.

The journal particularly excited interest because of one article by Professor Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,”[2] which more than any other single work established the paradigm style for the economic analysis of law. Prior to this article, Law and Economics (not so named as yet) was a hodge-podge of economics articles about law with differing styles and methodologies. After that article a field emerged which could be characterized by recognized canons of scholarship and excellence.

For several years after the appearance of this article, as scholars digested its significance, there was a period of extraordinary excitement. The word gradually went around indicating that Law and Economics now had an agreed-upon methodology and the substantive basis for a new and powerful type of analysis. It might be added that it was primarily that article which earned Professor Coase a Nobel Prize in economics in 1991, since in addition to helping develop Law and Economics as a field, it also spawned an entire new type of economic analysis, so-called “transactions-cost” economics. Rarely was an award so universally applauded.

The second major event was in many ways more important in the development of the new field than the first. Just as Coase had invented an almost universally applicable methodology for analyzing legal issues, so did then Professor, now Judge, Richard Posner’s revolutionary textbook, Economic Analysis of Law, [3] actually demonstrate the universal applicability of economic analysis to every area of law. Never again would Law and Economics be thought of as exclusively the domain of antitrust and corporate law. Now its domain was the very heart of the legal system, torts, property, contracts, domestic relations, procedure, even constitutional law.

With almost relentless zeal, Posner demonstrated that every field of law was susceptible to economic analysis. More important, his work made it clear that no other cross-disciplinary approach could have anything like the pervasive applicability and impact of economics. Much of the analysis in Posner’s first edition of Economic Analysis of Law was weak or even superficial from the point of view of technical economics’ But in no way can this detract from the real significance of the book as the first great comprehensive treatise on the economics of law. And while there have been many, many texts on this subject since, none has come even close to the majesty and influence of Posner’s. It can truly be said that this work created the agenda for Law and Economics scholars, and discussion of Posner and his works has become almost a cottage industry in itself.

The third event in this list is less important for its intrinsic merit than it was as a message to the world that Law and Economics had an even more significant imprimatur than that of the University of Chicago. This was the appearance in 1970 of Guido Calabresi’s The Costs of Accidents: A Legal and Economic Analysis [4]. This work represented the first book length effort to deal comprehensively with the economics of a single area of law, in this case personal injury law.

While its conclusions are still very much in doubt and in spite of the fact that it did not have the overwhelming influence on the field of, say, Director’s work in antitrust, Calabresi’ s book was enormously important for the development of Law and Economics. It represented, for the first time, a major work by a recognized legal scholar not at or even connected with the University of Chicago. It did not matter that the mode of analysis bore considerable resemblance to that done by Chicago writers; now Law and Economics could proceed without the pejorative tag “Chicago School” always attached to it. And for a great many legal academics, that was extremely important, indeed even crucial. Thus Calabresi’s work joins the pantheon of great events in the development of Law and Economics because it certified to a skeptical academic community that it really was all right to do this kind of work.

The fourth event occurred in 1971, and, as will be seen, it provides an important link to the historical origins of the modern George Mason University School of Law. The event was the first offering of the Economics Institute for Law Professors, then a three-and-a-half week (later reduced to two weeks) intensive course in microeconomic theory taught by distinguished economists to a class of 25 law professors. No effort was made in the early versions of this course to relate economics directly to the law; that was to be left entirely to the law professors, each armed with a copy of Posner’s Economic Analysis of Law.

From the beginning, this course or institute, affectionately nicknamed “economics summer camp” or “Pareto in the Pines” (changed, after the move from Rochester, N.Y. to Miami, to “Pareto in the Palms”) was a great success. The course has been heavily oversubscribed almost every year, and to date close to 600 mostly American and Canadian law professors have completed the course. Many of these have become recognized scholars in Law and Economics, including such illustrious academics as Thomas Morgan, Warren Schwartz, Robert Ellickson, Ralph Winter, Robert Scott and Ernest Gellhorn, to mention but a few.

But the importance of the course does not lie with the few stars; rather the importance lies in the fact that there is not a major law school in the country today that does not have at least one professor who has been trained in the economic analysis relevant to law. Largely a result of this program, too, every major law school in the country offers at least a basic course in Law and Economics, and few schools would not expose their students to the work of such scholars as Calabresi, Coase and Posner. Whole fields such as corporation law, antitrust and bankruptcy, and large parts of fields such as torts, property, environmental law and contracts, are taught in many law schools heavily from a Law and Economics perspective.

There are today eight journals devoted exclusively to Law and Economics scholarship; numerous conferences every year within the field of Law and Economics; a European, a Canadian, and an American Law and Economics Association; probably 20 or 25 comprehensive Law and Economics texts in various languages; and Law and Economics Working Paper Series published by probably 10 to 15 law schools. In other words what we have witnessed is the birth and development of a major intellectual field of worldwide interest and profound import. And now it is time to turn our attention to the more purely administrative aspects of the development of the George Mason University School of Law.

The Law and Economics Center

The success of the economics institutes for law professors led me to think that more programs integrating law and economics would also be well received. So in 1974, with the approval of the then Dean at the University of Miami Law School, the late Soia Mentschikoff, I founded the Law and Economics Center at the University of Miami. This too was a milestone in the development of Law and Economics as a recognized academic field, since, among other things, it served as a kind of clearinghouse or association for people interested in the field.

Regular conferences brought together for the first time the scattered scholars, both in law and in economics, largely working alone at various institutions around the country. The Center, or as it is better known, the LEC, published a newsletter reporting all academic developments in the Law and Economics field, including news of working papers in Law and Economics which were just then beginning to be circulated. By 1980 this newsletter had a circulation of over 1200 academics in the United States and abroad.

The LEC remained at Miami for six years and then it moved to Emory in 1980. When I assumed my present position as Dean at the George Mason University School of Law in 1986, the Center became an integrated part of the Law School, and it continues to offer the same programs as it had previously. This Law and Economics Center, now located at George Mason, was the first and most prominent of the many academic centers in Law and Economics that exist today, including those at such schools as Yale, Chicago, Stanford, Columbia, Harvard, Berkeley, Northwestern, Virginia, and Duke.

In 1976, while still at Miami, I started a new program modeled after the very popular Economics Institute for Law Professors, this time offering basically the same fare to groups of federal judges. From its beginning this program has proved enormously popular and useful to the federal judiciary. At the present time more than 400 federal judges have completed at least the basic course, and most of them have returned for one or more of the five advanced courses the LEC offers. In recent years the Center has also branched out by offering a course in basic science and scientific method to federal judges as well.

These courses for federal judges have been so popular that for most new judges today the Economics Institute is thought to be almost a requirement. These judges acknowledge that their own formal education did not really equip them for many of the issues that they regularly deal with as federal judges. Not only do these courses introduce judges to the basics of price theory, economic notions of cost, and the theory of the firm, but they also introduce many judges for the first time to the basics of accounting, statistics and finance. In fact the latter set of topics was so well received by the judges that it is now offered as a separate “advanced” course. We shall revisit this “Quantitative Methods” course again, as we see the influence that this program for federal judges had on the development of the curriculum at George Mason.

Today the LEC has an annual budget of approximately $900,000 and is directed by Professor Richard F. Fielding, who both directs the various teaching institutes and conferences and directly engages in most of the fundraising for the Center. At present the Center offers the six courses mentioned to federal judges, three courses for law professors, and an introductory law course for academic economists. In addition to this the Center usually administers two or three academic conferences a year and publishes a variety of materials.

The Genesis of the George Mason Plan

From 1968 to 1974 I was Kenan Professor of Law and Political Science at the University of Rochester. I was also director of planning for a new law school at the U. of R. In that capacity, and in consultation with some of the most eminent legal scholars in America, I developed a new plan for a law school. Unlike the traditional school, but more in line with general university practice, this one was to have a series of specialty programs, not unlike “majors” in an undergraduate school.

Each student was to go through law school specializing either in economics, political science, science and technology, or behavioral science. The courses, as well as the particular orientation of individual classes, would be determined by the interdisciplinary specialty chosen by the student. Coincidentally this program bore considerable resemblance to that adopted by the University of Rochester’s medical school over forty years previously. Then it had been felt that medical schools were too mechanical, or, as it is sometimes put, too vocational, to give the students the breadth of education required by modern medical science and practice. Rochester was the second medical school in the country to adopt this “interdisciplinary” approach after Johns Hopkins first adopted it from the German medical schools, particularly that at Heidelberg.

This approach is generally in line with what the legal realists had been seeking. Their major criticism of American legal education was that it simply was not intellectual or scholarly enough and that lawyers needed to know a great deal more than merely how to find and argue about appellate opinions. A number of distinguished educators were also called in to Rochester to analyze and critique the program. Generally it evoked tremendous enthusiasm and was found to be eminently workable. The principal concern, one which proved to be correct, was that it sought to do too much for starters, and that beginning with one specialty might be more feasible than trying to begin with four.

But despite all the enthusiasm and official approval that this plan generated at the University of Rochester (only the local bar, wrongly predicting that it would create too many lawyers in Monroe County, strongly opposed the plan), the University did not have sufficient funds to embark on such an ambitious and expensive new school. By 1973 it became clear to everyone that this plan was not within the fundraising abilities of the University and would not be pursued. In 1974, I also felt that if I were to return to legal education, it would not be at Rochester.

But in 1971 I had started the summer Economics Institute for Law Professors, which by 1974 was quite well known and successful. It was from this beginning, as previously mentioned, that the Law and Economics Center was developed at Miami and moved to Emory in 1980 and George Mason in 1986. But through all of this I carried copies of the extensive study for a new law school I had done for the University of Rochester.

The likelihood of starting a law school of the type proposed seemed small because it seemed that it would require starting from ground zero. An existing, traditional faculty would simply have to make too many revisions and changes in their style and in the content of their courses for them to adopt such an idea. And yet, with some obvious modifications necessary to adapt the plan to George Mason’s circumstances, this is the plan that became the modern George Mason University School of Law.

Much of the credit for what occurred at GMU belongs to the University President, Dr. George W. Johnson. He repeatedly said that he did not want “just another good law school.” Rather, consistent with his entire style at this new, innovative and burgeoning university, he wanted to be at the cutting edge, to set new models for other universities, and to take chances in order to move George Mason’s reputation along in a hurry. When he heard in some detail my idea for a law school, he is reported to have said to an associate, “whether Henry Manne comes here or not, that is the kind of law school we want.”

There were basically three strands to the overall program introduced at George Mason. One of these was the idea of specialization, first developed in the Rochester plan but adapted to the special circumstances of GMU. The second was the interdisciplinary approach, strongly suggested by the whole tenor of the Legal Realist movement but in no small measure also reflecting my own educational and professional experiences. And finally was the particular influence of the courses developed for law professors and federal judges by the Law and Economics Center.

Specialization by Large Professional Field

American law schools, it has been noted frequently and correctly, are fundamentally conservative institutions. Obviously, this does not refer to any ideological position but rather to the fact that they rarely make or even tolerate fundamental change in the way things are done. This is probably inherent in the mode of governance of most law schools, since individual interests in courses and curricula are jealously guarded as faculty prerogatives, and thus it is difficult ever to generate a majority in favor of significant change.

The effects of this on legal education have been stultifying at best. Consider the fact that by the middle of the 1930’s the norm for a degree from an American law school had become three years (first after three years of undergraduate training and then by the 1960’s after an undergraduate degree). Now, nearly 60 years later, the norm is still three years of law school. But consider what has happened in that period. It is probably safe to say that the absolute amount of law, measured by almost any quantitative standard, is at least 100 times what it was in 1932. The dominant form of law practice has changed from individual practitioners and very small firms, to giant multi-branched, international, mega-firms sometimes employing over 1,000 lawyers, every one of whom is specialized in some area of law practice.

The last point is the salient one for our purposes. American legal education and its standard curricula reflect a kind of law practice that in the future will be regarded as almost an anachronism. Even such formerly “bread-and-butter” fields of law as criminal practice, personal injury, and domestic relations are today dominated by men and women who really do very little else. (I do not want to exaggerate this point; obviously there are still many fine solo practitioners who will take whatever case a client brings in.)

The analogy to the general practitioner in medicine in an era of specialization in diagnosis and treatment is apt. Modern law, like modern medicine, is overwhelmingly characterized by practitioners who tend to know more about one area of their practice (or type of practice) than about others. It is not that they do not need a wide range of knowledge about many different fields; it is rather that unless they are comparatively better in one thing than in all others, they will not be able to function successfully in today’s milieu. Like it or not, that is a fact of professional life in late twentieth-century America. Unfortunately, with very few exceptions, no American law school until George Mason made a comprehensive effort to train students for this kind of professional reality.

It has long been true in the large law schools in the United States, or those that have very large budgets, that students could elect a number of courses in one area of law. This is sometimes even announced in the catalogue as an “area of emphasis,” and all the courses in one area will be listed together. This has been especially true of tax law and international law, with a smaller number of schools listing such areas of emphasis as environmental law, health law, business law, litigation and a variety of others. Unfortunately what characterizes this degree of “specialization” is the mere fact that the courses can be listed under one rubric. In no sense are these schools offering an integrated curriculum, carefully planned with a professional specialty in mind.

That is not what was done at George Mason. The idea was to design a three-year curriculum for a student willing to select an area for specialization but who would accept the faculty’s decision as to which courses to take and in what order. In effect the “track” students, as they have become known at GMUSL, give up the right to select a large number of electives during law school in exchange for having a planned and coherent curriculum in one area.

This kind of integration of courses allows an advantage unknown in the schools that allow students to elect a number of courses in one area of emphasis. By integrating courses as the student progresses, each course builds on those going before, thus allowing greater and greater sophistication in the work done because every student has had all the prior material. In the typical system followed in most law schools, except for courses that demand a prerequisite course, every elective has to be pitched to the novice in that field. The result of the GMU approach is a much more thoroughly trained student in the area of specialization selected.

But specialization has its costs, and no one can function without a broad view of all areas of law any more than they could in medicine. The practical effect of the last point on the program at GMU is a compromise between the necessity for a general background (especially what will be sufficient to prepare the graduate to study for and pass a state bar exam) and the desirability for some knowledge more specialized than is usually possible in most American law schools. Luckily, as we can see, this compromise could be reached at a relatively small cost.

Law schools have long followed the practice of allowing most professors, certainly senior ones, to teach at least one course of their own choosing. The net result has been the proliferation in American law schools of a large number of often exotic, highly specialized (or having a narrow subject matter), and certainly not interrelated, seminars and elective courses. As this practice proliferated, a rationalization was invented for it, and schools began to rank themselves on the number of these special electives available to students. Naturally the bigger and richer a school, the more electives would be offered.

The argument has a certain superficial plausibility, since students will like the idea of being able to study any exotic subject that comes to mind. (Of course, what really comes to their minds is the particular electives listed, since in reality most students know relatively little about what might be valuable to them and what subjects might be offered that are not listed.) There is no reason to complain that this proliferation of exotica represents an irresponsibility of most law schools towards their students. It is often forced on schools by the fact of competition for faculty. But this practice has never been independently justified, and it never resulted from a carefully designed program to meet the educational needs of prospective lawyers.

Still, this curricular practice served a valuable purpose as far as George Mason was concerned. Cutting back heavily on these courses allowed the necessary compromise between appropriate general legal education and the addition of specialized courses. Basically at GMUSL, there are very few freestanding, and narrowly focused elective courses. Students not in one of the specialty tracks still have a wide range of courses they may elect, but this list is heavily determined by the needs of the specialty tracks, not by the narrow interests of particular professors.

Thus students in the tracks take approximately one-third of their courses in the form of specialized, required track courses and two-thirds from among a fairly orthodox list of courses. In the end all that has been lost in the process of rationalizing GMUSL’s curriculum is the hodge-podge of electives most other students face, now replaced by a different list serving an end other than the research, or intellectual interests, of particular professors. The entire track curricula will not be described here, since that already appears in detail in other materials published by the Law School. Suffice it to say that in 1992, approximately 35% of GMUSL’s entering students elected one of the tracks, but since two of the tracks were only started in the fall of 1992, it is anticipated that the stated goal of up to one-half of our students in the tracks will be reached with the first year of a full three-year complement of students in all the tracks, in 1994-95.

One important aspect of the track system should be noted. The complaint is sometimes made that specialization narrows the education students get and thus deprives them of some intellectually broadening consequence of electing special, detailed and varied seminars. Probably that argument is exactly backwards. Without some degree of depth (not one course) in a field of law, a student comes out of school without any real intellectual sense of how the law actually operates. Only by seeing one field in depth can a student be well prepared for what the practice of law is actually like. And the greater sophistication that comes with in-depth study will serve the student well regardless of what field of law he or she eventually specializes in.

Because of its novelty and the necessity to educate potential employers to this development, George Mason University has emphasized the vocational aspects of specialization. But its greatest advantages are really pedagogical. It is not for nothing that every undergraduate in America, with minuscule exceptions, must “major” in some area. The underlying notion is the same as that at George Mason. The ideal education will be a compromise designed to give both generality and focus, both breadth and depth, and both survey and specialization.

This approach has proved popular beyond expectations. George Mason’s law school receives an astonishing number of applications (nearly 4,000 last year) for a school so newly “announced,” and, more important than that, graduates of George Mason are receiving job offers both in practice and in judicial clerkships in numbers and quality that would be satisfying at many much older and better established law schools. By all standards, moral, intellectual and market, the specialization program at George Mason has proved enormously successful.

Cross-Disciplinary Aspects

The original plan for the University of Rochester called for academic rather than professional-field specialization. Students were to “major” in economics, political science, technology or behavioral sciences. Each of these “fields” was to be organized somewhat as a department in a liberal arts college, with each department’s faculty qualified to select colleagues only in that field. Each of these separate sections would be comprised of people who had common intellectual interests and who could understand and evaluate each other’s work.

This approach was not, however, physically feasible at George Mason University. It required close collaboration between the law faculty and the university faculties in the cognate disciplines. This was perhaps doable at a small, unified campus like Rochester’s, but George Mason’s law school was located in Arlington, while the main campus of the university, containing all the other relevant departments, is almost 15 miles away, in Fairfax, Virginia. Clearly the “academic specialization” part of the Rochester plan had to be adapted to this geography.

The adjustment made is one that probably would have been required at Rochester, though for a different reason. To develop serious collaboration with other parts of the university, unless the law faculty can do double duty, is a very expensive proposition, since it requires more faculty than is the case in traditional law schools. It is doubtful that any school could begin with four such areas of specialization. It was clear that George Mason would not be able to have more than one intellectual specialization (not to be confused with the professional specialization represented by the “track” system), and it was equally clear that that field would have to be one in which law faculty could do “double duty.” Economics was selected for George Mason for a variety of reasons.

First, as we have seen, economics has proved to be the most powerful and applicable cross-disciplinary tool to use in collaboration with law. There simply are more fields of law that can use economics profitably than is true of any other discipline. Second, it is more likely that an entire law school can be staffed by law professors with some meaningful background in economics than with those with any other discipline. There has been vastly more serious training of Law and Economics-oriented law professors than is true of any other cross-disciplinary field. Third (and this factor cannot be denied or minimized), Law and Economics was the one field that I was qualified by my own experience to develop, staff and evaluate.

A Law and Economics orientation for all new faculty obviously makes recruitment a more difficult undertaking than if no such emphasis existed. But at the same time it has also made the school much more attractive to potential recruits who do have this background. A larger problem was what to do with the ten or so professors who remained from before the new program was introduced. Various means were used to bring those professors into the intellectual life of the school.

Two actually had strong economics backgrounds (including one with a Ph.D.), two would probably retire within a few years, and two embarked on graduate study of economics at the Law School’s expense while teaching a half load. (This experiment has proved particularly felicitous, as these two are receiving Ph.D.’s.) This left four who teach in areas where economics simply has less relevance than in other areas of law, such as public international law, Church and State, and clinical trial practice. But all the faculty, including new additions, are invited - and most accept - to take the summer economics institute for law professors, now held each year in Hanover, New Hampshire.

The downside of all this is a certain narrowness of intellectual focus in the Law School. As we have discussed earlier, that is the inevitable cost of any degree of specialization, and the hard trade-off decision has to be made. But it should be made consciously and after serious consideration, not by default and the accident of faculty selection and politics as is the case in most law schools. We believe that the loss is more than compensated for by the additional educational advantage of this degree of specialization. Certainly the purely legal part of the education is much more focused and far more sophisticated than if the school attempted, as many do, to be all things to all people. Aside from the obvious truth that George Mason could not afford that luxury, it often has the effect of creating dilettantes who are conversant with many areas but who do not really excel at any, unless they happened to master one field somewhere else.

As we have already intimated, the major vehicle for this intellectual specialization in Law and Economics was the selection of faculty. Actually little else had to be done, since a sufficiently intellectual and research-oriented professor could hardly fail to convey this interest, and indeed enthusiasm, to students. Probably George Mason is one of the few law schools of any size that does not offer a separate course in Law and Economics. Instead, after an appropriate introduction, students find that nearly every course has a Law and Economics flavor that reinforces their instruction in those courses.

The appropriate vehicle for getting students of any undergraduate background introduced to Law and Economics is one of the more successful of the many innovations at George Mason. It is also a reflection of the valuable tie-in between the School’s programs and those offered by the Law and Economics Center for federal judges and professors. It was decided that it would be inappropriate to teach a beginning course in economics as a prelude to the first work in Law and Economics, though this approach is followed by a number of law schools. This has the unfortunate effect of making the economics (or other cross- disciplinary areas) seem somehow separate from the real work of the law, a somewhat parallel but largely irrelevant field. The George Mason approach was designed to overcome just that sense of compartmentalization often characteristic of other law schools’ interdisciplinary work.

The solution was found in a course offered to federal judges, the advanced course in accounting, statistics, econometrics and finance. This experience had shown us that this material, integral to any understanding and practical use of economics, was properly seen as an integral part of a sound legal education.

The vehicle selected was a course entitled “Quantitative Methods for Lawyers,” a six-hour law course required of all George Mason students in the first year. The course addresses the legal use of statistics, accounting, finance and economics. But it is definitely not a straightforward course in these subjects. It is a law course, taught heavily with cases and other legal materials, demonstrating the absolutely critical relevance of this material to any practice of law. It by no means conveys the message that this material is somehow separate from or in any way more important for resolving disputes than is the more traditional legal fare.

The whole thrust of the course is to demonstrate that one cannot do many things in law without this material, whether it is calculating damages, understanding structured settlements, arguing antitrust points, calculating statistics for discrimination cases, or arguing cogently about corporate takeovers. Naturally some straight didactic materials in these non-law areas are necessary to get students started, but the emphasis is on the relevance of this material to legal situations in the real world. Too often this important part of law practice is simply ignored in law schools for the simple reason that not many law professors know how to do it.

But there is another aspect of the program at George Mason that distinguishes it from that at other law schools. After this beginning, with fairly simple accounting, statistics, finance and economics, almost every professor in the law school reinforces and extends this learning in other courses. No one belittles it or suggests that somehow it is “less important” than cases or statutes. The net effect of this is a very sophisticated form of education with every course reinforcing the learning of previous ones. The result is to produce lawyers with a far deeper understanding of legal materials than can be true when the educational approach is more uni-dimensional. As simple proof of the success of this approach, it has been observed how difficult it can be for transfer students to keep up with the intellectual level of work done by non-transfer students at George Mason.

While the professional specialization of the track system could be adopted at most law schools (with a lot of hard work by the existing faculty) and while an introductory “Quant” course could be offered, it still would not have the impact of the George Mason program for one reason. At George Mason the entire curriculum is permeated with a distinctive intellectual flavor, emphasized and developed by almost every professor. Without this consistent approach by almost an entire faculty, it would not be possible to develop the depth and sophistication of learning that characterizes George Mason. A Quantitative Methods course in another, more traditional school would simply stand by itself, not as an integral part of every course that follows it. And specialized “tracks” would be a mere agglomeration of some- what related courses rather than a consistent, integrated academic experience leading to much greater learning.

Conclusion

As law schools in the United States face greater and greater financial constraints, the financially weaker ones will have to find approaches that allow them to survive against stronger, wealthier and more prestigious schools. We believe that the program at George Mason shows at least one way that such schools may be able to compete effectively. It does not matter whether the tracks are in business fields, as they are at GMU, or whether the intellectual focus is economics, also as at GMU. What matters is that these schools will need to find some niche in the academic marketplace that will allow them to do a comparatively better job in that area than most other schools.

Thus law schools are likely to develop a package of specialties in, for example, environmental law, personal injury law and health law. These three, as with the business-oriented tracks at George Mason, will overlap enough in some of their required course offerings that the whole thing will be affordable. The cross-disciplinary focus for such a package might well join work in physiology, biology and environmental sciences. Students would also learn about the culture of the medical profession, the nature of scientific method and the theory of insurance as it relates to health care.

True, these students would not know the niceties of international trade economics or the latest theories of constitutional interpretation. But they would be better trained lawyers, better able to serve their clients and society. If the experiment at George Mason University can influence other schools in this fashion, its real benefits will extend far beyond the obvious success it is already enjoying.

- It should perhaps be noted that during the very time period that Director’s influence was most pronounced at Chicago, 1949-1952, I was a student there and became personally familiar with much of this story.

- R. H. Coase, “The Problem of Social Cost,” 3 Journal of Law & Economics (1960).

- Richard A. Posner, Economic Analysis of Law (1st ed. 1972). “The work appeared in its much more sophisticated fourth edition in 1992.”

- Guido Calabresi. The Cost of Accidents: A Legal and Economic Analysis (1970).

Henry G. Manne: A Biography

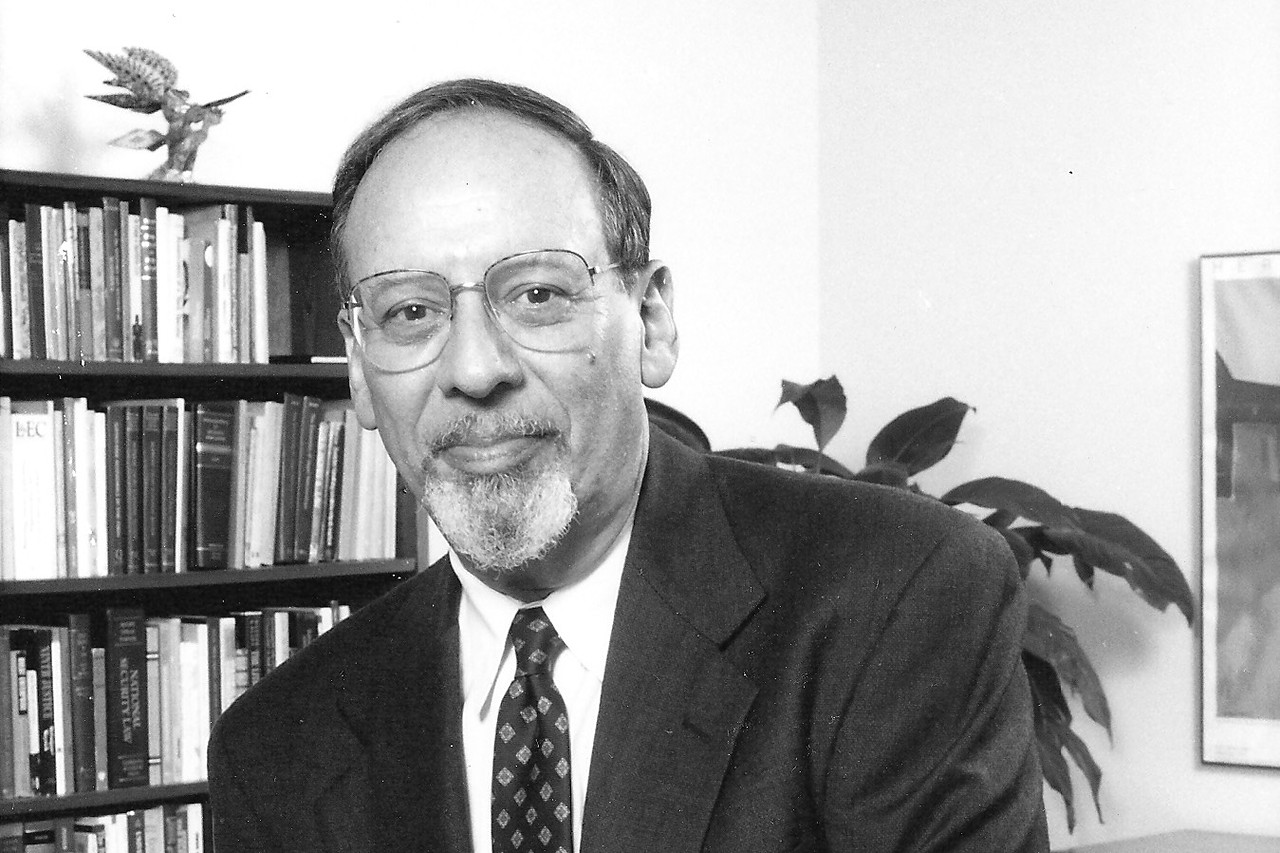

Lauded as a cultural laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia, former Mason dean Henry G. Manne was the driving force behind the many innovations in legal education implemented at George Mason.

Professor Manne was designated one of the “founders” of the field of law and economics by the American Law and Economics Association. He launched the Law and Economics Center at Emory University and the University of Miami before bringing it to George Mason.

His monograph, An Intellectual History of the School of Law, George Mason University, traces the development of the law and economics movement and highlights the special contributions made by George Mason University School of Law to the movement. Professor Manne’s other writings include such seminal works as Insider Trading and the Stock Market; Wall Street in Transition (with E. Solomon); and “Mergers and the Market for Corporate Control”, Journal of Political Economy, April 1965. Professor Manne also designed and implemented at George Mason the nation's first system of fully integrated law school specialty track programs.

In August 2012, Dean Manne gave an oral history of his life, including his time at the Law and Economics Center, to the Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society. An audio recording of the interview and transcript are available on the Society's website: audio (mp3); edited transcript (pdf).

He received a B.A. from Vanderbilt University (1950), J.D. from the University of Chicago (1952), J.S.D. from Yale University (1966), LL.D. from Seattle University (1987), and LL.D. from the Universidad Francesco Marroquin in Guatemala (1987).